A proposal to enhance the risk assessment of the Dutch Early Warning/Early Action process

Over the course of the last three decades, countless scholars, diplomats and experts have sought to develop reliable ways to predict and prevent violent conflict and instability. These efforts have yielded a vast array of analytical instruments, ranging from indices that measure various proximate and structural causes of instability to forecasting models that estimate the probability of an outbreak of violent conflict.

Predicting and preventing violent conflict and instability

Presently, there is a great deal of data available ranging from better measures of political violence and better predictors of violence. Moreover, as data sciences advance, social scientists have been able to develop new models and refine their predictions. However, as such tools proliferate, so do the challenges for policymakers.

First, more data does not always mean ‘better’ data. Key indicators such as on political inclusivity, local grievances and competition are often still not readily available.

Second, more data and better methodologies have not always meant a better insight into conflict risks. While we have generally become better in predicting the continuation and intensity of ongoing conflict, it remains a major challenge to predict which countries will become unstable and when.

Third, perhaps the biggest problem is that even when having a clear insight into conflict risks, converting these insights into actionable policies remains difficult. In these instances, it is often not a lack of information or insufficient early warning signals per se that pose the key obstacles, but rather the ability to convert these data points into policy-relevant analysis and to identify relevant entry points for preventive efforts.

The Government of the Netherlands

These challenges are particularly relevant for the Government of the Netherlands. In 2018 the Government of the Netherlands prioritised conflict prevention as the first goal of its Integrated International Security Strategy, emphasising the importance of ‘a solid information position, with up-to-date and detailed information, based in part on innovative big data solutions for peace and security’.

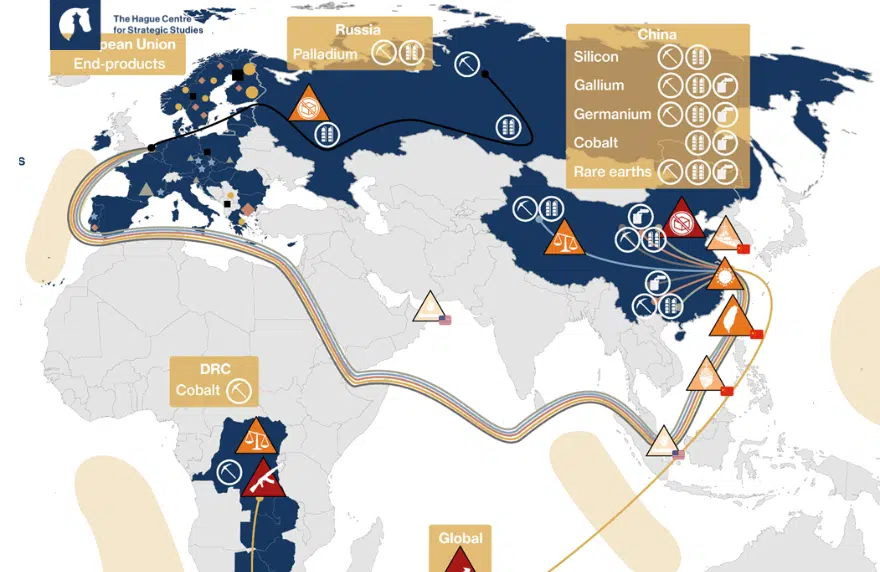

Since the adoption of this strategy, the Ministries of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and Defence (MOD) have made significant investments in enhancing their ability to provide early warning and early action (EWEA). As part of its focus on ‘Data for Peace and Security’ (D4PS) the MFA has developed a number of data-driven tools that rely on an array of indices and forecasting models in order to compile long lists, short lists and watch lists of countries that are at increased risk of experiencing violent conflict or instability. The process builds on a methodology proposed by the Clingendael Institute in 2020.

Within the framework of the multi-annual PROGRESS research programme, the Dutch MFA has commissioned the Clingendael Institute to provide recommendations on how to build upon these existing data tools and strengthen the capacity of the authorities to assess the risk of violent conflict and instability. The specific objective was to make better use of the available quantitative indicators and data and to design a process that did not require in-depth individual country assessments. As such, the method was meant to inform the decision to go from a long list to a short list of countries with likely higher risks. After that, more targeted in-depth studies could be commissioned.

The report

This report, hence, devises a method for a general scan of countries in order to identify those countries that should be monitored and studied in more detail. The focus of the report will be on the first, exploratory phases of the process, where open-source quantitative indices are used to make a selection of countries that should be further examined. In doing so, the report addresses the three challenges mentioned above (missing data, conflict theories and how to act) by providing a detailed methodology to enhance early warning processes.

To this end, this report will a) discern different types of indices (i.e. those that observe and predict violence and instability, and those that seek to explain it); b) categorise the vast array of indices on drivers of conflict and instability through a concrete proposal on how to cluster and interpret them; c) operationalise these quantitative insights within the context of the Dutch EWEA process; and d) integrate the quantitative data into a qualitative analysis process through an expert workshop and the use of several rounds of Delphi surveys.

Reading guide

In order to meet these objectives, this report is structured as follows. Chapter 2 will set out the overall methodology of the proposed process. Chapter 3 critically examines the advantages and disadvantages of many indices. Chapter 4 then puts forward a proposal on how to cluster these indices into those that observe conflict and violence and those that measure the underlying drivers of conflict and violence. Moreover, it proposes a disaggregation of the latter group of indices into four clusters of the main drivers of conflict and instability. Finally, chapter 5 puts forward recommendations on how this data can be interpreted, visualised and subsequently used in a qualitative expert workshop.

Authors

Bob Deen, coordinator of the Clingendael Russia and Eastern Europe Centre (CREEC) and Senior Research Fellow at the Security Unit of the Clingendael Institute

Adája Stoetman, Junior Researcher at the Security Unit of the Clingendael Institute

Kars de Bruijne, Senior Research Fellow at the Conflict Research Unit of the Clingendael Institute