To choose or not to choose?

The Russian invasion in Ukraine has fundamentally changed the security environment in Europe. Member states as well as the EU and NATO have responded to the new challenges posed by Russia’s aggression, resulting in decisions that were deemed unthinkable before, such as the Finnish and Swedish application for NATO membership. Defence budgets have been further increased and the number of Allied countries realising NATO’s 2 percent GDP target on defence is growing. With defence budgets on the rise, there is an increasing risk of countries seeking national solutions to European capability shortfalls. Multinational defence cooperation is the tool to prevent this from happening and defence specialisation should become an important element in strengthening European military capabilities.

The term specialisation generates more opposition than support in the defence community

However, the term specialisation generates more opposition than support in the defence community because it has often been interpreted as a scapegoat for deliberately abandoning defence capabilities, driven by budget cuts and conducted in an uncoordinated way – specialisation ‘by default’ instead of ‘by design’. This form of specialisation makes a country fully dependent on other nations to provide the abandoned capabilities, which raises the issue of dependency and guaranteed access when needed.

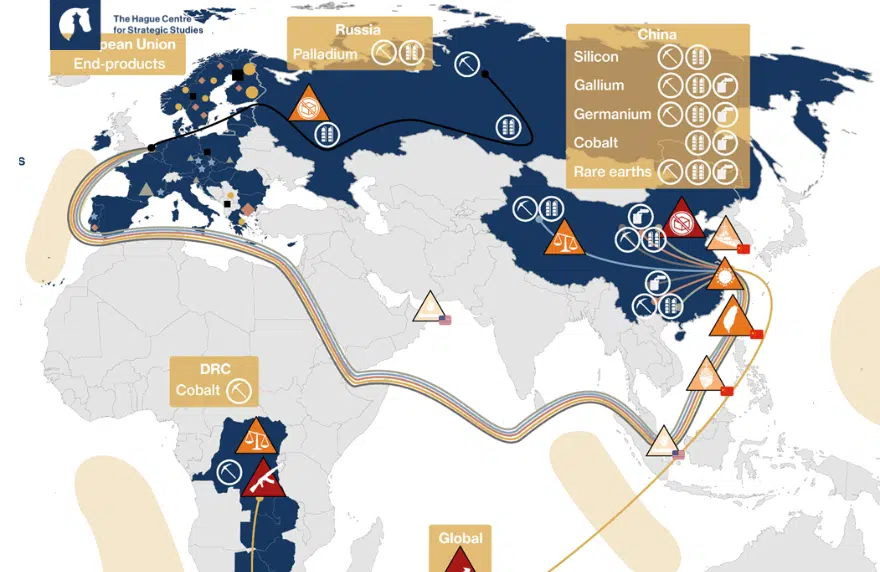

However, despite the controversy, various forms of specialisation and dependencies already exist, without being labelled as such. Smaller countries, with limited defence budgets, often rely on larger partners for the provision of certain defence capabilities such as missile defence or long-range strike capabilities. The rising costs of armaments, in particular high-technology weapon systems, also reduces the number of ‘haves’ versus ‘non-haves’. In some cases, pooling and sharing models have been developed for capabilities that countries cannot afford on their own. Examples are multinational pools for strategic transport and air-to-air refuelling: NATO’s Strategic Airlift Capability (SAC) with C-17 military transport aircraft and the Multi-Role Transport and Tanker (MRTT) pool operating military adjusted versions of the Airbus A330. Nations using drawing rights for aircraft are dependent on such a multinational capability. Dependencies on the capabilities of other states or multinational frameworks also exist for space-based secure communications, strategic reconnaissance and intelligence. Another format is a capability collectively provided by ‘have nations’ to ‘non-have nations’.

For example, the Baltic States are fully dependent on NATO partners to provide fighter aircraft for air policing on rotation. An already existing form of agreed mutual dependencies is the Belgian and Dutch specialisation in training and maintenance facilities – concentrated in either of the two countries – for minehunters and frigates respectively. This far-reaching dependency has also led to the common acquisition of follow-on capabilities.

History, geographic location and strategic culture are factors of great importance to defence specialisation

Amongst others, history, geographic location and strategic culture are factors of great importance to specialisation, resulting in the different capability profiles of countries with ‘specialised or niche capabilities’ or ‘specialisms’. France and the United Kingdom emphasise their strength in expeditionary capabilities, as a result of their former worldwide empires and continuous overseas military responsibilities. For that purpose, they operate aircraft carriers amongst other capabilities that are deployable over long distances. Germany has an orientation on strengthening above all its posture for collective defence, in particular heavy land forces. Landlocked nations, such as Hungary, have armies, but no navies. The Czech Republic has a niche capability in defence against chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CRBN) threats. In a somewhat different vein, the integration of the Dutch-German land forces is progressing towards increasing mutual dependency, based on geographic proximity and close military cooperation over decades which has strengthened mutual trust and confidence between the two countries.

Thus, the issue of specialisation has to be placed in a wider context of multinational defence cooperation and it can take various forms. The common feature of all varieties of specialisation is the element of dependency.

Specialisation by default to specialisation by design

When moving from specialisation by default to specialisation by design, countries should not operate in isolation from the two key international organisations for safeguarding and ensuring European security: the EU and NATO. First, in designing specialisation formats, the capability needs as defined by both organisations have to be taken as the point of departure and should direct the capability areas for exploring options for specialisation. Second, both organisations should steer, coordinate and monitor specialisation efforts as part of their responsibilities in capability development. In that regard, the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP) should incorporate multinational targets in addition to national targets. The EU should also incorporate multinational capability efforts in its Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) in order to steer collaborative programmes and projects even better.

The authors

Dick Zandee, Head of the Security Unit at the Clingendael Institute

Adája Stoetman, Research Fellow at the Security Unit of the Clingendael Institute